relatively free to do as he liked without interference.

Abenaki Inheritance

In Wallace's time, the backwoods people lived not very differently from their Indian neighbors, in bark houses and simple log cabins put together from the forest. Throughout the settlement of Orange County, it appears that Indian families lived amongst the white settlers, perhaps on the outskirts of the villages, perhaps making claim to various plots of land (Blaisdell, 1980: 109)5, and also intermarrying with the settlers. A number of native families in this watershed area, for instance, are so by virtue of an Indian wife (Howard Knight, 1988-89). This intermarriage indicates a peaceful exchange between settlers and Abenaki. Moody has indicated to me that the Abenaki women were a strong force in their culture; perhaps Vermonters' right to live on this land in part was secured by relationships with Abenaki women. In any event, women as socializers pass on their values and ways of being most powerfully--even without conscious effort, patterns of culture, of behavior and world-view are imparted to children.

In frontier settlement, away from puritanical control, many whites became "Indianized", or "squaw men", living on the outskirts of white society (Hallowell, 1963). To the dismay of Angloamerican leaders, who regarded the natives as heathen savages, a significant number of whites preferred Indian ways to European (Calloway, 1984: 163-164, 170-171)(Axtell, 1981)(Axtell, 1985). Furthermore, to counteract their population declines, the Abenaki captured and adopted many whites, particularly young people, some of whom became Abenaki wives and mothers, and even Chiefs (Heard, 1973)(Huden, 1956, 199-200). In fact, the Abenaki had had quite a long time of association with Europeans, since the beginnings of the fur trade. Contrary to stereotypes of Indians as savage or exotically primitive, many of the Abenaki were heavily involved in intercultural exchange and change well before the British settlers arrived in Orange County. European goods such as firearms, clothing, metals, etc., had been commonly adopted, as well as medicines and Chrisitianity (Haviland, 1981: 210-219)(Cronon, 1983: 103-104). Building construction (Roger's raiders burned down a church at St. Francis), and even literacy were known to the Abenaki. One White chief is said to have been fluent in both French and English (Huden, 1956, 201). Likewise, one of the most famous Indians of Orange County, "Indian Joe", had a father who..."owned considerable property, including 'horses and jacks, neat cattle, and other domestic animals'...(Blaisdell, 1980: 93).

Repeatedly writers speak of the last Abenaki, the dying out, or disappearance of the people (Huden, 1955: 25)(Haviland, 1981, xvi). The Abenaki denied their seperate heritage certainly to outsiders, sometimes even to themselves. Yet, informal polls by Huden (1955: 25) and Michael Caduto (1988)6, indicate that at least 5-10% of Vermonts have Indian ancestry, and researchers continue to find modern Abenaki in their midsts. Genealogically, on can find the trace of Abenaki inheritance amongst many people in the backwoods, particularly in the area I decided to study. because in Western thinking Indianness is attributed to a particular material culture, political structure, or phenotype, as Indians adopt European economics and institutions, they are seen as having disappeared. This seems to be a form of wishful thinking by a culture which continuously assumes it

will wipe out all other cultures, by virtue of inherent superiority. The anthropological version is to see evolution as a form of extinction (Clifford, 1986: 122-113). In fact, however, the Abenaki and Vermonter cultures merged, mutually absorbing each other, as people intermarried, took on each others values, participated in community activities, etc.

In Newbury, for instance, only three towns north of Thetford, General Bailey, and presumably his associate Colonel Johnson, "always befriended the Indians...never one overlooked the Indians in the daily rations...(Hemenway, 1871: 926)" presumably for military service as allies with the French and Americans against the British. Likewise, across the river in Haverhill, "...Captain John Page...lived on friendly terms with the Indians of Cohos...(Blaisdell, 1980: 92)". At the beginning of American settlement thirty Abenaki men and some familiy were in the area, and "...By 1780, there were over 100 Indians living in Newbury, besides a number of Indians from St. Francis who made seasonal visits for hunting and fishing...(Blaisdell, 1980: 90)." Likewise, decades after white settlement, Abenaki continued to live in Wigwams in outside of Newbury, using the land to hunt, fish and trade (Blaisdell, 1980: 108) and there is at least one story of natives protecting their land from desecration in West Fairlee (ibid, 109). Today these Abenaki have local descendants (Moody, 1988-89).

It was during this time, i.e. mid-nineteenth century, that a number of changes were occuring which may have encouraged further assimillation. To begin, the Canadian border was finally closed (Knight, 1988-89). Some Abenaki, who had fought against the British, preferred to stay and become Americans (Blaisdell, 1980: 94). Second, after 1850, the early settlers began to emigrate. Hill tops which had been massively cleared proved not to be agriculturally adequate, and land prices plummeted as the settlers abandoned their farms and went west (Wilson, 1936: 124-138). The pines now began to grow back. Deer were reintroduced in 1878, after their numbers had been severely reduced (Johnson, 1980: 90-91). This may have made Vermont more suitable to live in, although the original ecology which had supported their livlihood was destroyed7.

Finally, economic opprotunities opened up for non-land owners. After the war of 1812, "...certain families returned to ancestral location in the United States to hunt, fish, and guide surveyors and sportsmen...(Day, 1978: 152)." This return may have been a slow process:

"...From about 1865 to about 1950, the ash-splint basket industry brought considerable number of Abenakis back to the resort areas of...United States...Guiding gradually replaced hunting and trapping...until about 1970...(when the)...lure of industrial employment started small Abenaki communities in several Northeastern United States cities...(ibid)"

Many Abenaki survived through migrant labor and seasonal trade, appearing to be gypsies or tramps to townspeople, often following the Connecticut8. Others became loggers, small farmers, road workers, railroad workers, etc. and were able to establish themselves as permanent town residents (Moody, 1978: 58, 59).

Thus, as the flatlander settlers left for better prospects west, the people most tied to the land found a niche for themselves, through work. The back country of Vermont at this time was not an economically

desirable place to live, and local towns and people were relatively undisturbed by outside

influences or controls. In reviewing town and census records, it appears that many of the present families which I associate with local native Vermonters became established from this late nineteenth century period. Instead of calling themselves Indian, they became part of Vermont's working class, at least to outsiders 9.

THE OMPOMPANOOSUCK WATERSHED TODAY

In my research, I found a distinction in character between the West Branch of the Ompompanoosuc River, which travels through the villages of Strafford, and the area lying between the East Brand and Miller Pond/ Skunk Hollow road, which I think reflects the cultural difference discussed about 10.

A. West Side:

Here one sees old farms and names of the descendants of early Orange County settlers, such as the Silloway (Bradford), Eastman, Phelps, Wood, Moody, and Kendalls. I do not as yet have records on the Strafford inahbitants after the initial settlement period, so that I don't know the origins of other townspeople's names such as the Campbell's, and the Lewis' whose farm is for sale. Some, but not all, live in old typical white farmhouses, trimmed with green, visible from the main roads of the village. These traditionally represent middle class Vermonters, who worked in stores, had tidy farms, minded their own business, and smiled politely.

The land here, besides being connected with an open valley and centers of population, has a certain light quality, with few pines, and in some places excellent views. Effort has been made to keep the land cleared and tended, although at the present time no one I interviewed was involved in farming as their primary source of livlihood; with the exception of the Johnsons who moved here from Connecticut 20 years ago to start their orchard. However, there are a number of places which do have animals or which advertise maple products in this area, such as Gile Kendall's beef cattle along the Tunbridge road, or the Finn farm being Huntington Horse Farm.

Amongst those I interviewed, the Silloways keep their land in current use, to avoid taxes, but are too old to farm it themselves. They sold some land to their children, who resold it to strangers. They don't plan to sell anymore. The Eastmans do not farm either, I don't believe, nor do their nearby relatives: although they do grow a garden, some apples, syrup, and flowers, as well as cut wood for heat, and clear brush. Formerly Rowland used to hunt deer. One of his sons lives adjacent to him, the other in South Royalton, as well as a duaghter who was visiting while I was there. Their land is for sale. In both cases, the children appeared to live relatively nearby, near enough to visit and to help with tasks such as weatherizing and repairs. Galdys Wood Silloway takes in washing from the local restaurant.

Whereas the Silloways and Eastmans do not appear rich in any urban sense, they have fairly newer model cars, pretty flowers (i.e. pansies), and keep a need exterior appearance. They were polite when I introduced myself, and above all, seemed welcoming. Likewise, the Coburns I have met seem

friendly and gentle. Objectively, the Silloway's house is "in need" of a coat of paint--it is the typical white with green trim and fading paint farmhouse, comfortable but not ostentatious, which I have come to associate with classic Vermont.

The Eastmans live in a trailer built onto to fit into the land as is commonly done in the Upper Valley. When I visited, Rowland, the senior family member, wore the famous green farmers pants and spit dark liquid constantly, while talking virtually nonstop. His daughter's front tooth was discolored blue, her husband had long hair and they seemed typically working class. I had great difficulty understanding Rowland, as he has a very strong accent, reminding me of Scottish. At least two of his relatives live in West Fairlee, one being the constable at Beanville road living amidst a junkpile and sporting an ornery reputation, the other operating a garage. Eastmans, however, are "everywhere".

The Coburns come from an old Vermont family, and operate the one store and gas pump in town, as well as house the post office and Twin State Bank. I met Stuart Coburn, cousin to the store owners and resident of Vershire, during hunting season which he was driving his green pick up truck slowly on a back dirt road wearing his checked jacket, with a requisite rifle in the back. I spotted him easily as a 'typical' 'Vermonter'. (He smelled faintly of alcohol.) We talked for awhile about who owns the land, how the spot nearby used to be good for hunting, etc. I have spoken with other Coburns in the store, or observed them at Strafford public meetings.

B. East Side

Here, the people and the land are connected to Vershire/ West Fairlee via Miller Pond and Beanville roads, but especially to the Thetford center via Sawnee Bean road, and by family and cultural ties. The energy of the people and of the houses appears different. This area feels very isolated, which it is, from the village. While there are some impressive farmhouses and large tracts still owned by one family, what stands out for me are the smaller dwellings, here and there, not packed together as in town or the village, but distinct. Often they have large collections of rusted, abandoned vehicles, including cars, trucks and farm equipment, lined up or scattered with no apparent organization along the road or waterfront, several old sheds which are halfway fallen back into the ground, gaping holes through grey deteriorated wood, no particular landscaping, usually at least one dog. Some adjectives which come to mind to describe this area are, besides isolated: simple, minimal, modest, upretentious, used. Or even tired, rusty, dilapidated, junky, low income, atypical in color--strong blue, green, possibly tacky. Many, although not all, of these houses appear to have been built within the last forty or so years. One might find a shack, small cabin, a trailer, or unoccupied camp. Often the laundry is hanging out; there seems to be no overriding interest in impressing visitors, at least not with shiny new material objects.

For instance, where Sawnee Bean meets Miller Pond in Strafford, Ernie Stone used to live, until a tractor tipped over on him this Fall. He lived in a small trailer, with countless junk cars sinking into the earth, scattered along the road frontage and even back aways, along with farm equipment and falling down sheds of grey wood and high grass. The general feel was of disorder, randomness, collapse, returning into the earth, and age. Down Skunk Hollow, one passes Ralph Coutermarch, Sr.,

with his several trucks, tractors, old cars, old bed springs, chair frams and other discarded objects or work projects decorating the dirt yard. His work horses are in the barn adjacent to his house, which is typically faded white with green trim. Since he is just barely off the road, a passerby can't miss him, and he has a reputation of 'roughness' locally.

The appearance of the homes might be a reflection of poverty, as well as the cost and trouble of hauling broken or unused items. However, I found that the supposed clutter revealed a practical purpose, such as the repair of a vehicle, done by the owner himself, on the spot. Or some places may have piles of logs and stumps, reflecting the logging livlihood of the inhabitant. Many of these people work long hours, seven days a week, so that adorning one's home would be a foolish luxury. One backwoods person told me explicitly he preferred his home to be comfortable, livable, so one did not have to worry about the furniture. Like one's land, the home is expected to be functional, not a work of art. In Grow, the statement is made that "...Most farmers...don't bother to paint their houses...(1960:90)" suggesting again a rural practicality and custom. Ernest Herbert in the novel The Dogs of March (1979) suggests that collections of junk cars symbolize wealth, as a potential resource, i.e. parts cars, back ups against break down, etc. The retention of old appliances and vehicles might be seen as opposing a society which tosses anything slightly unwanted into the trash, without thought to its cost. Another person I spoke to gave me an even more direct reasoning. He said he left his yard that way the way he did to discourage taxes. He says he'd just as soon leave the road from as messy as possible, and fix the inside, thank you.

When I have driven down these backroads for the first time, I have gotten the feeling I was being watched, like an intruder--often by children. As an example, the last time I was walking along Barker Road, which comes out of Sawnee Bean in Thetford Center, I noticed a dark-haired woman in an old gold station wagon and dingy cream jacket driving down the hill to Post Mills Village. She crossed my path on her way back up and turned int the drive of a small green tar asphalt shingled house sporting a hand printed cardboard sign warning "Ugly Dog". Along the river, to the right, I counted 12 vehicles abandoned. After she turned, the snow plow came by, and then she went back to wait for her kids from the school bus. She then drove up Pero Hill road. I walked by the house, and noted four red letters: PERO--on the front side. I turned around and walked back down Barker Road. As I was walking, the snow plow stopped and asked if I wanted a right-rather unusual, I thought. At first I declined; then thinking it might be one of the four Thurstons who live on Barker road, I accepted, only to find he was in fact a Pero. He said he'd seen me around town, and took me past my car and twice up another road before depositing me. Perhaps he just wanted company--later I wondered if weren't also "checking me out".

As one walks further along Sawnee Bean, one finds more land posted by members of the Pero family. Likewise, going in from Tucker Hill via Whippoorwill, past the chief of the local Abenaki (Howard Franklin Knight Jr.), one comes to Pero posted land, which continues to Sawnee Bean. All of this area--the whole hill, was owned by the Pero family. According to a neighbor, it is now being sold off in pieces, and at the top of Pero Hill are four brand new and very large houses. Reginald Pero, the father of 14, lives in a modest white house with pretty red Christmas decorations.

As I begin to investigate my area more, it became clear to me that this area is inhabited by

people who are related to or have ties with one or more of the Abenaki families in Thetford. Miller Pond lies at the Western edge of what Howard Knight, the current chief of the local Abenaki band, identified to me as the Thetford Abenaki territory, and Tucker Hill delineates the southern edge. He told me that Joe Pero, when he died (Oct. 13, 1983 in Thetford Center, Orange County, Vermont), told them about this area's history and Indian sites. Some of these were recently excavated by the Vermont archaeological society, in opposition to a proposed hydro-electrical plant. Apparently, the original Pero was a shrewd business man, and was able to control this area, away from the main village centers. People like Howard could live at the edges of the land, and be insulated from outsiders. Recently though, Howard has felt hemmed in by new neighbors, as many of my other interviewees did.

Besides the Pero family, there are or have been other Abenaki related families in the area. The enclosed map (not included in the Court Records re: Arthur Marchand) indicates the former presence of the Dodge and Pierce families in the back areas of Strafford. Likewise, the Mannings occupy a number of ajoining spots. Most notably, at the foot of the Pero ridge off of Route 113, before Sawnee Bean, there is a large cleared area, a number of houses/ trailers, logging rigs and old school buses, etc. parked behind the main Manning house. There are also Mannings along Miller Pond and Alger Brook. Formerly, the Mannings' grandmother lived on the Dodge orad, near where John Manning still hunts today. Howard F. Knight Jr. himself lives on the end of a road connected to Pero land, and so on.

Perusal of birth and marriage records for the town of Thetford reinforced the notion that many of the families along Skunk Hollow and Barker Road who live in some of the distinctive sites of the type described above are related in some way either to the Abenaki families I am aware of, descended from families whose history included significant relations with the Abenaki, have a current history of interaction with Abenaki, or have French Canadian ancestry, which may include native ties as well.

For instance, in reviewing Thetford town records, and from recent interviews, I determined that the following relationships exist:

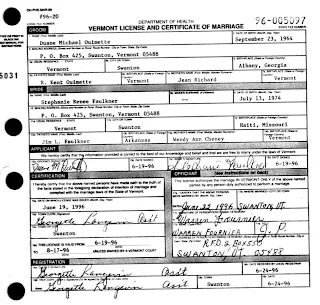

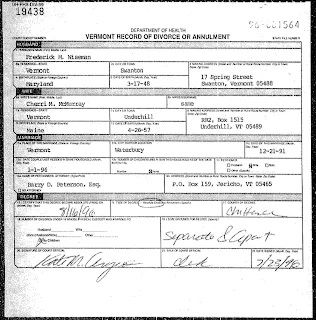

Harry Cook Pero m. Edith Olive Godfrey (Dec. 08, 1912 in Thetford, VT) (gpa of 14 sons, inc. Reggie Reginald Arthur Pero, born April 01, 1928 in Thetford, VT)

Marjorie Grace Pero m. Ralph W. Ward (on March 11, 1936 in Thetford, VT) (Crystal Ward on Skunk Hollw interviewed)

Gladys May Pero m. Geore E. Hodge on May 14, 1932 in West Fairlee, VT (child 1935)

Richard Allen Hodge m. Elaine Mary Stone (1961) (both families on Skunk Hollow Road)

Helen Louise Godfrey m. Wayne Doyle on Aug. 06, 1960 in Thetford, VT (related to trapper interviewed)

Marion Jane nee: Waterman (1st sawmill/ Barker Road) m. Homer Albion Cook on July 21, 1918 in Norwich, VT

Marion Corabelle Cook m. Howard Frankin Knight Sr.

Knight m. Godfrey (1885)

Knight m. Glaser (Barker Road) (child 1963)

Arvin Clarence Manning m. Eileen Joyce Palmer ( Dec. 09, 1950 in Thetford, VT)

Alford Charles Manning engaged to Nancy Eileen Bailey (presently) Married Sept. 30, 1972 Thetford

Ina Inez Lena Bailey m. Stuart Carroll Coburn (interviewee) on Sept. 22, 1956 in Union Village, VT

Coutermarsh m. Marden (1938)

M. Herbert G. Cook m. Vaun C. Pierce (May 26, 1929 in Thetford, VT)

Of these 18 surnames, then have been identified to me as having Abenaki ancestry or relatives. Some of these families can also be traced back to the original settlers. Some, however, do not appear in the official Thetford records or Vermont census until the 1800's (Jackson, 1976-84). This could be

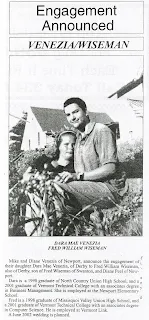

due to incomplete records, migration from other towns, or cultural assimilation. I do not have comparable records from the Town of Strafford, although the cultural connection has always been strong between the two towns (Fifield, 1988). At least two families of this area moved from Strafford to Thetford. perusal of the Vermont Census Index for 1790 through 1890 shows that in Swanton, the central settlement for the Missisquoi Abenaki who are actively seeking recognition and aboriginal rights in Vermont, lived a Manning (1890) and some Pero's-(including a Joseph in 1850--but no Pero listed in Vermont before 1830, and none in 1890 11)(Jackson et al, 1976-1984). This suggests that some of the backwoods Thetford families have genealogical ties with other Vermont Abenaki communities, and perhaps engaged in migration/ intermarriage at that time. The grandparents of the present chief of the Thetford band apparently lived up by Joe's Pond in Danville, named after the famous patriotic Indian Joe mentioned earlier in this paper (Knight, 1989). Finally many of today's "native names" appear as active in Thetford after the period of abandonment of farms mentioned earlier in this paper, and after many Abenaki had adopted Euroamerican houses, dress, jobs, etc.

The recurrence of a few family names on the mailboxes, as well as the intermarriages between those families and the families I know to be part of the Abenaki band gave me a sense that people have consciously or otherwise tended to stay close together, intermarry, and to stay within this particular geographical area for both cultural and ecological reasons. The land is Abenaki land, in the sense that the ancestors, the history, the ecology, and the descendants are there. But it does not fit the definition in terms of exclusiveness, as non-native families live amongst them. Like family bands with loosely knit organization, where people are free to wander and associate, free to vote with their feet, and free to travel in search of better prospects--these people are linked to the land in spirit, in the sense of an ash tree belonging to the earth which gives them substenance (Bruchac, 1987: 2-5).

Nearly all of these families live within close range of Sawnee Bean road, which joins Miller pond and Pudunk with the Ompompanoosuc. Fishing traditionally has been an important resource for Abenaki; today the Missisquoi have been staging fish-ins to demonstrate the importance of this activity to them. It is consonant with the historical and archeological record of settlement patterns of the Abenaki (Haviland, 1981) 12 that they live clustered near both a once navigable river (befor the dam was built in Union Village) and Miller Pond, still used by trappers and fishers today. I noted that my interviewees still value hunting and live near or own property near good or popular hunting spots.

Furthermore, most of the people living in this area do not have extensive farmland. Rather, their homes often are tucked away at the very end of a woodsy dirt road, on the side of a piney, undeveloped slope, or simply lack the impressive quality of an old farmhouse, being instead a moderate dwelling. In general, if farming was practiced, it did not appear to have been on a large commercial scale and I do not remember observing much in the way of domestic animals, other than cats and dogs, although here and there were some horses.

Besides Abenaki, a number of people living in this territory appear to have French Canadian ancestry/ neighbors. Traditionally, the French and Abenaki were close allies, and lived amongst each other, often intermarrying. In Strafford, Countermarsh of course sounds French. I was also told he is Native American, and a number of his comments suggests this possibility. For instance, he

views some of his neighbors as "white farmers", and perfers to grow Indian corn. In Thetford, two Paige families, one sporting a front yard Madonna indicative of French Catholic heritage, live down the road from Howard Knight. Likewise, Reginald Pero lived next door to the Mathieu family, which could be French, although my interviewee mentioned only her Italian ancestry. Finally Claude (Thurston) is a French name. Furthermore, the facct that many of the Abenaki, French-Canadian and backwoods families I identified in Thetford wee also those consistantly delinquent in taxes, in past decades (Thetford Town Reports: 1937, 1941, 1949, 1955, 1970-1979) suggests a continuing cultural affinity between these neighbors, at least economically and/ or politically. Possibly this is due to poverty, possibly due to resistence, or even ornery character--in that case it fits the idea of the outlaw Indian, misfit, petty little problems with the law, nothing serious, which Howard Franklin Knight Jr. referred to as an Abenaki trait, living in white society.

Another family, Thurston, has a strong reputation in Bradford for fighting with the Mannings; and in this area a Thurston was reputed to have burned up Coutermarsh's logging rig, over a dispute regarding timber and land rights. The Thurstons and Mannings and Mannings and Paiges in Bradford and Thetford respectively, apparently have quite a reputation for "rowdy" behavior, amongst townspeople 13. In Post Mills, right off Sawnee Bean, there are four Thurston dwellings, just dowhill from the Pero lands. These include an old house, but also some small do-it-yourself places recently put together with inexpensive, unpainted and unstained wood, on rock foundations, with holes in their walls, and the like.

In looking back through the census records of the 1800's, and later through the Thetford town reports of the 1900's. It appears that the names and associated professions which I now associate with local Native Vermonters, became well established in Thetford after 1880. Some names involved in my research, either from surveying mailboxes, or from conversations/ interviews, which date in the Thetford area from at leasts from the late 1800's are Coburn, Barker, Blake, Evans, Cook, Palmer, Paige, Waterman, Manning (Sharon) and Pero. Throughout town reports for Thetford from 1900 on, one finds the Knight, Bailey, Godfrey, Pero, Palmer, Cook, Paige, Huggett and Vaughan families consistently involved in road work, cemetery digging, donating logs, and tree warden activities. Today, the Mannings and Peros are loggers. Baileys do well drilling and excavation. Huggett Mobil is a well-established garage in East Thetford. The Vaughan family, has in recent years come under fire for monopolizing the gravel source for the town of Thetford for years. The Cook family's truck likewise can always be seen at the site of Norwich road work--and as one resident put it--"they own the town". Art Pero operates a snow polw/ truck in Thetford Center, while Wayne Manning runs the town Garage in South Royalton. Other self-employed, working families from the watershed whose ancestors did not work for the town, include the Bigelows, whose trucks can be seen in Hanouver, Eastman's garage in West Fairlee, and Steve Ward's garage in Vershire. In Thetford, Claude Thurston oversees the work of Art Pero, and plows the roads as well. In Strafford, Coutermarch reputedly used to log; today he trains and shows work horses who pull logs. Of the above, nine of the working families mentioned were identified as part Indian, by the local Abenaki chief Howard Knight Jr., or by John Moody (1988-89). two others' ancestors had historically recorded, positive relationships with the Abenaki. Their descendants appear to be continuing the pattern of close association.