TWENTIETH CENTURY

Twentieth Century Claims of Abenaki ContinuityThere is very little to say about the Abenakis in Vermont in the twentieth century

until the 1970's. From 1900 to 1974 they were invisible, if they were here at all. Most of the twentieth century material will be addressed in response to the specific criteria, but a brief overview here will provide background.

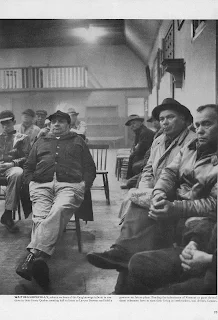

There was no noticeable Abenaki community in Vermont, let alone Franklin County, from 1900 to 1970. It was only in 1970, with the increase in ethnic consciousness across the U.S., that Abenakis became detectable. In 1974 a group of individuals re-constituted the tribe and created a tribal Council. The petition credits the associations made through Veterans groups after WWII as the immediate precursor to the social and political reorganization of the St. Francis/Sokoki Band of Missisquoi in the 1970's (Petition Addendum: 123). The petitioner concedes this was re-creation, re-emergence, and re-organization of the community (Petition Addendum: 126). One of the first things the Tribal Council did was push for state recognition. Its efforts led to the Baker report to the Governor of Vermont in November, 1976. 45. This report prompted the outgoing Governor Thomas Salmon's to issue an Executive Order recognizing the Abenakis in Vermont. State recognition was short-lived. Two months later, in January, 1977, newly elected Governor Richard Snelling revoked the Executive Order.

The Eugenics Survey of Vermont

The Second Addendum to the Petition, filed with the BIA in 1995, lists one of its

________________

FOOTNOTE:

45. The reaction to the Balser report by scholars of Abenaki history and ethnology is discussed below in the section on Criterion (a): 1974 to 1981.

sources as the Vermont Eugenics Survey (Second Addendum:9). The Second Addendum describes the survey as an "insidious and discriminatory program" aimed at "the eradication of mental and moral 'defectives' within the community." It states that despite this, the archives of the survey are "extremely valuable in demonstrating the ancestry of the Native-Americans in Vermont who were especially targeted to be victims of this program" (Second Addendum:9). The notion that Indians were targeted by the Eugenics Survey is but a mere mention in the petition: however the idea has loomed large in the petitioner's public arguments for tribal acknowledgment. The ways in which the petitioner has exploited the Eugenics Survey are explained below and in the Affidavit of J. Kay Davis, which is attached to this Response.

For example, in a press packet entitled "The New Vermont Eugenics Survey,"released in February 2002, Frederick Wiseman, an Abenaki spokesman, wrote:

Once long ago, in the 1920's, post WWI tide of xenophobia turned inward to haunt inter-ethnic relations in the "the whitest state in the union." Dr. Henry Perkins of the University of Vermont and a group of Anglo intellectual and civic leaders founded the Vermont Eugenics Survey. Its purpose was to study Eugenics Survey. study groups of Vermonters (called the "unfortunates"), who by their very existence needed more state assistance, social programs, institutionalization, legal fees, etc than the "old stock" Anglo Vermonters. In order to stem this "drain" of resources, the survey began a study of the family histories of "horse trading, basketmaking" Abenaki lineages. The Eugenics Surveys dream was realized in 1931, when Vermont passed the Act for Voluntary Sterilization. (Wiseman 200-2:1).

Wiseman's book, Voice of the Dawn, is filled with similar rhetoric geared to bolster public support for federal acknowledgment. There he sought to explain away the invisibility and lack of information about the Abenakis by blaming the Eugenics Survey:

Soon the lens of genocide was trained on the Gypsies, Pirates, and River Rats, 46. as well as other ethnic groups. Employing the latest genealogical research and statistical record keeping techniques, the survey added new technologies to the list of ancient genocidal procedures used by New English authorities against the Abenakis. In addition, they provided social and police organizations with lists of families to "watch." Unfortunately, the social gulf between elite Anglo culture and the village dwelling River Rats and Pirates was not so wide that they could entirely escape notice. Major Abenaki families at Missisqoui were especially at risk. The more "hidden" families and the Gypsies partially escaped unheeded—for a while. But then began ethnic conflict incidents as Gypsies and Pirates had their children taken from them. The theft of children and the hatred emanating from the burning cross and Ku Klux Klan rallies are still recalled by Abenaki and French Canadian elders in Barre, Vermont. Any family who still had thoughts about standing forth as Abenaki, due to the tourists' continued interest in our arts and culture quickly retired to obscurity as the tide of intolerance rose. We continually needed to be on our guard with the police, the tax man, and the school board, the eves and ears of the survey. (Wiseman 2001:147-48).

The notion that the Eugenics Survey caused the Abenakis to hide their Indian

identities became current in the late 1990's when it made its way into a history kit published history by the Vermont Historical Society in 1998:

History books have long claimed that the Abenaki "disappeared" from Vermont. While some Abenaki did leave Vermont for Canada, many others remained. As the Abenaki began to speak French or English and adopted European dress, historians of the nineteenth century assumed that the Abenaki had vanished. The Abenaki families who remained in Vermont survived in a variety of ways. Some lived a nomadic life and were called "gypsies." Others remained on the outskirts of their communities and lived off the land as they had for centuries hunting, fishing, and trapping.

From the 1920's through the 1940's the Eugenics Survey of Vermont... sought to "improve" Vermont by seeking out "genetically inferior peoples" such as Indians, illiterates, thieves, the insane, paupers, alcoholics, those with harelips, etc....As a result of this program, Abenaki had to hide their heritage even more. They were forced to deny their culture to their children and grandchildren. (Vermont Historical Society 1998:31).

__________________

FOOTNOTE:

46. The first annual report of the Eugenics Survey used the terms, "Gypsy," and "Pirate" to describe Survey "Gypsy," some of the families it portrayed. The term "River Rat" is not found in the reports (Eugenics Survey of Vermont 1927:8).

The concept of the eugenics survey driving the Abenakis underground was trumpeted again at the time of Chief Homer St. Francis's death in 2001. One newspaper article reporting on St. Francis's passing said:

However, the argument was never made by any scholars of Indian history in Vermont before 1991. Jean S. Baker's Report to Governor Salmon in 1976 does not mention it, nor does Ken Pierce's 1977 History of the Abenaki People. John Moody's manuscript on Missisquoi in 1979 does not insinuate any link between the Eugenics Survey and the invisibility of the Abenakis; he doesn't even mention the survey. This is very surprising since all three of these authors based their writings on extensive interviews with people claiming Abenaki heritage. All three of them earned the trust of their informants, yet they never disclosed the survey as a significant factor in Abenaki history.

Most importantly, neither the original petition for federal acknowledgment, filed in 1982, or the first Addendum to the Petition filed in 1986 contains any mention of the Survey. Only the Second Addendum, dated 1995, refers to it, but without any of the arguments of its effect on the invisibility of Abenaki families. To unpack the building of this myth, a more detailed examination of the Eugenics Survey of Vermont is required.

Established in 1925, the Eugenics Survey was one of many undertaken in the United States during the 1920's and 1930's. Vermont's was headed by Henry F. Perkins, Chairman during by of the University of Vermont's Zoology Department. The Survey issued five reports between 1927 and 1931. It conducted surveys of town and surveys of people. It created

genealogical pedigree charts of twenty-two families in depth, and began charts for dozens more (Dann 1991:6, Gallagher 1998). The survey led to the creation, by Henry Perkins, of the Vermont Commission on Country Life (Dann 1991:6, 17-19).

One focus of the Eugenics Survey was the physical and mental condition of theVermont population. The authors saw embarrassingly large numbers of Vermonters rejected from military service in World War I on physical and mental grounds. State officials wanted to know why so many were rejected (Ainsworth 1944:11 ). The State officials were also concerned about the population losses due to emigration out of the state, and the lack of industrial changes in Vermont compared with other New England states (Ainsworth 1944:10-11). Meanwhile, they saw rural towns becoming depopulated, causing a deterioration of the social structure (Gallagher 1999:45.)

The reports of the survey and its work led to further study of population trends by the Vermont Commission on Country Life. That Commission attempted to answer these questions: What are the motives of those who left the state? What are the motives and vocational choices of those who stayed in Vermont') What are the motives of those who have moved into the state and what contributions have they brought? (Perkins, H.:1930:2-3 ). Survey authors advocated reforms in family welfare, public health, economic aid to rehabilitation, and education, but also endorsed sterilization as a matter of social policy (Ainsworth: 17).

One method used by the Eugenics Survey to analyze population trends in Vermont was to classify towns by certain characteristics. In a section of the survey papers labeled "Towns Suggested for Study," is a map labeling towns as "declined in some way," "desirable or progressive," "outlanders," "summer people," or "original stock" (Eugenics Survey of

Vermont [1929]). In the northwestern part of the state, the area where the Abenaki claims are greatest, two towns were labeled for study because they had "declined in some way." These were Swanton and Fairfax. The narrative descriptions accompanying the map indicate the reasons for examining them—and they have nothing to do with possible Indian populations. Rather, Fairfax was suggested for study to determine "why the theological seminary left and what was the effect of its departure on the town" (Eugenics Survey of Vermont [1929]). The reasons Swanton was cited for study were succinct:

Swanton presents an interesting problem. During the war, there was a large shirt (?) factory there and the town was thriving. Now the factory stands empty, and in spite of the fact that there is apparently everything to do with water power. some marble, and available building the town is on the decline.

It would be interesting to see whether or not the town was pushed beyond its capacity during the war or whether it still has possibilities for a steady prosperity. (Eugenics Survey of Vermont [ 1929]).

There is nothing in these descriptions that would lead one to believe the targets of the Eugenics Survey were areas of Indian habitation. Furthermore, the nearby towns of Highgate, Franklin, and Sheldon, claimed to be havens for Abenaki families, were not suggested for study at all.

The only other northwestern Vermont towns suggested for study were on the Lake Champlain Islands: North Hero, Grand Isle, and Alburgh. All three were labeled as having summer people and outlanders. They are noted as having two distinct classes of people—old settlers and new French Canadian families. The survey notes that population was declining as most of the young people were leaving. Once again there is no mention of Indians (Eugenics Survey of Vermont [1929]).

There is nothing in the Eugenics Survey papers that indicates that Indians were targeted by the survey. If any group was targeted, it was the French Canadians (Davis

Affidavit, Attachment A:9). The Third Annual Report of the Eugenics Survey of Vermont published in 1929, included a list of "Some English Corruptions of French Names." The survey printed this list because "the spelling of a name is seen to change through successive generations. It is easy to see that such discrepancies might throw one off the track for a long time. The implication is that the surveyors were particularly interested in following the French Canadian "track" (Eugenics Survey of Vermont 1929:5). Perkins was enthusiastic about studying French Canadians. He sought grants to further the study of this group, and hoped to develop data correlating the degree of French-Canadian ancestry with "mental testing, educational attainment, and various cultural factors" (Gallagher 1999:95). Vermont's focus on French Canadians continued into the 1930's. The Works Progress Administration guide, Vermont: A Guide to the Green Mountain State said that "[s]ince 1900 the largest single immigrant group has been the French-Canadian. As early as the 1930's this element began replacing the Yankee farmers in the northernmost tier of counties; today they constitute approximately one-quarter of the population there (including second generation) as compared with thirteen percent of the State's total" (Works Progress Administration 1937:51). This group was by far the largest of any immigrant group. 47. An impressive study of racial interaction in Vermont arose out of the midst of the Eugenics Survey. This was Elin Anderson's We Americans: A Study of Cleavage in an Eugenics Survey American City (1937). While Anderson had worked under Perkins for the eugenics survey for seven years, she brought an entirely different interpretation to the material. Rather than years

______________

FOOTNOTE:______________

47. After the French-Canadians' thirteen percent portion. the next largest group was the non-French Canadians, which comprised three per cent of the state's population. No other group even reached one percent (Works Progress Administration 1937:52).

promote the pioneer-stock Yankees as the epitome of society, she exposed their narrow-mindedness toward other ethnic groups (Anderson 1937:155-56). Her study sought to understand the reasons for cleavages within communities, to determine the extent to which they were ethnically based, and to look for ways to move beyond those divisions. Anderson began by surveying a sample of residents from six of Burlington's ethnic groups: French-Canadian, Irish, Germans, Italians, Jews, and Yankee "Old Americans" (Anderson 1937:272). They were surveyed using a set of questions that inquired into the extent the immigrant groups interacted with each other, were assimilated into the mainline culture, or were intentionally kept separate.

The model Survey form was designed for French-Canadians, the others wereadaptations of it (Eugenics Survey of Vermont [1932-1936]). This main shows the prominence of the focus on French-Canadians as the dominant immigrant group. One question specifically listed fourteen other ethnic groups and asked for the respondent's perception of them. The fourteen groups listed included French Canadians, Irish, Americans/Yankees, English Canadians, Italians, Jews, Germans, Syrians, French, Scottish, Greeks, English, Scandinavians, Chinese, and Negroes (Eugenics Survey of Vermont [1932-1936]). There was no surveying of attitudes toward Abenaki Indians, or Native Americans of any kind. They were not enough of a recognizable entity in Burlington in the 1930's to be part of the study.

The first published source to draw a connection between the Eugenics Survey and the Abenakis was Kevin Dann's 1991 article in Vermont History, "From Degeneration to Regeneration: The Eugenics Survey of Vermont, 1925-1936." There Dann noted a connection between the survey and the Abenaki: