St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of Vermont Abenakis:

Proposed Finding - Summary Under the Criteria

Page 20

CONCLUSIONS UNDER THE CRITERIA

(25 CFR 83.7)

Evidence for this proposed finding was submitted by the SSA and the State, and obtained through some limited independent research by the OFA staff to verify and evaluate the arguments submitted by the petitioner and interested parties. This proposed finding is based on the evidence available, and, as such, does not preclude the submission of other evidence during the comment period following the finding's publication. Such new evidence may result in a modification or reversal of the proposed finding's conclusions. The final determination, which will be published after the receipt of any comments and responses, will be based on both the evidence used in formulating the proposed finding and any new evidence submitted during the comment period.Executive Summary of the Proposed Finding's Conclusions

The proposed finding reaches the following conclusions under each of the mandatory criteria under 25 CFR Part 83:

The petitioner does not meet criterion 83.7(a). The available evidence demonstrates no external observers identified the petitioning group or a group of the petitioner's ancestors as an American Indian entity from 1900 to 1975. External sources have identified the petitioner on a regular basis only since 1976. Therefore, the petitioning group has not been identified as an Indian entity on a substantially continuous basis since 1900, and does not meet criterion 83.7(a).

The petitioner does not meet criterion 83.7(b). The available evidence does not demonstrate the petitioning group and its claimed ancestors descended from a historical Indian tribe, and therefore the petitioner did not establish that it comprises a distinct community that has existed as a community from historical times until the present. The petitioner has not provided sufficient evidence to establish that a predominant portion of the petitioning group has comprised a continuous community distinct from other populations since first sustained contact with non-Indians. The available evidence indicates that the petitioner's organization was only established in the early 1970's. Since that time social interaction has been limited to a small portion of the group's membership. Therefore, the petitioner does not meet criterion 83.7(b).

The petitioner does not meet criterion 83.7(c). The petitioner has not provided sufficient evidence to establish that it or any antecedent maintained political authority or influence over members as an autonomous entity since first sustained contact. The available evidence indicates that the exercise of political authority, formal or informal, has existed within the group only since the mid-1970's. Since that time political influence has been limited to a small number of members, who do not appear to have a significant bilateral relationship with the rest of the membership. Therefore, the petitioner does not meet criterion 83.7(c).

The petitioner meets criterion 83.7(d). The petitioner has presented a copy of its governing document and its membership criteria.

St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of Vermont Abenakis:

Proposed Finding - Summary Under the Criteria

Page 21

The petitioner does not meet criterion 83.7(e). The petitioner submitted a membership list dated August 9, 2005, which was received by the Secretary on August 23, 2005. This list named 2,506 individuals, 1,171 of whom were designated as current, full-fledged members. The petitioner has not provided sufficient evidence acceptable to the Secretary that its membership consists of individuals who descend from a historical Indian tribe or from historical Indian tribes which combined and functioned as a single autonomous political entity.The petitioner asserts that its present membership descends from the Missisquoi, a Western Abenaki tribe of Algonquian Indians that during the colonial period occupied the Lake Champlain region around the town of Swanton in northwestern Vennont. However, the petitioner has not provided sufficient evidence to establish that a predominant portion of the petitioning group descends from that entity or any other historical Indian tribe.

In addition, the petitioner's current membership list, dated August 9, 2005, and received by the Secretary on August 23, 2005, is not properly certified, and in many circumstances does not provide the full name, maiden name of married women, date of birth, and current place of residence of all members as required by the regulations. No evidence has been submitted for more than 90 percent of the membership to demonstrate that those individuals have applied for membership or even know they are on the membership list. Therefore, the petitioner does not meet the requirements of 83.7(e).

The petitioner meets criterion 83.7(f). The petitioner's membership is composed principally of persons who are not members of any federally acknowledged North American Indian tribe.

The petitioner meets criterion 83.7(g). Neither the petitioner nor its members are the subject of congressional legislation that has expressly terminated or forbidden the Federal relationship.

Failure to meet any one of the mandatory criteria will result in a determination that the group does not exist as an Indian tribe within the meaning of Federal law. The petitioner has failed to meet criteria 83.7(a), (b), (c), and (e). Therefore, the proposed finding concludes the petitioner does not exist as an Indian tribe.

St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of Vermont Abenakis:

Proposed Finding - Summary Under the Criteria

Page 22

Criterion 83.7(a) requires thatthe petitioner has been identified as an American Indian entity on a substantially continuous basis since 1900. Evidence that the group's character as an Indian entity has from time to time been denied shall not be considered to be conclusive evidence that this criterion has not been met.

Introduction

Criterion 83.7(a) is designed to evaluate the existence of the petitioner since 1900. The key to this criterion is identification of the petitioning group as an American Indian entity by an external source or sources. This criterion is intended to exclude from acknowledgment collections of Indian individuals that have not been identified as an Indian group or entity. It is also meant to prevent the acknowledgment of petitioners that have been identified as an Indian entity only in recent times, or whose Indian identity depends solely on self-identification. The regulations require substantially continuous identification since 1900, but provide no specific interval. Consistent identification is the primary requisite.

From 1900 to 1975, the available evidence demonstrates that no external observer identified the petitioning group now known as the "St. Francis/Sokoki Band of the Abenaki Nation of Vermont" (SSA). Thus, the petitioner was not identified as an American Indian entity on a substantially continuous basis during that 75-year period. External sources have regularly identified the petitioning group as an American Indian entity only since 1976.

Petitioner's Claims

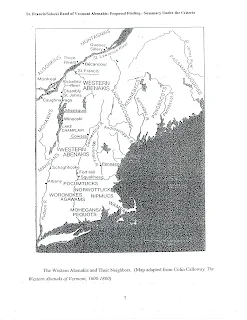

As described in its overview of the historical tribe, the petitioner claims to have descended as a group mainly from the Missisquoi, a historical Western Abenaki tribe of Algonquian Indians that occupied the Lake Champlain region of northwest Vermont during much of the colonial period.

Since its initial organization in 1976, the petitioning group has functioned or been identified under several names. In its 1980 letter of intent for Federal acknowledgment, the group used the name "St. Francis /Sokoki Band of Abenaki of Vermont." Over the last 29 years the petitioner and its governing body have employed various other names, including "Abenaki Nation," "St Francis/Sokoki Band," "Abenaki Nation of Vermont," "Abenaki Tribal Council," "Sovereign Abenaki Nation," "Vermont Abenaki," "Council of the, Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi," "Sovereign Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi," "Sovereign Republic of the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi," "Sovereign Republic of the Abenaki Nation International," and the "Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi St. Francis/Sokoki Band." For the analysis under criterion 83.7(a), all the available evidence from 1900 to the present in the record was examined to determine if any external observers identified an Indian entity, by any of these names or otherwise, composed of the petitioner's members or claimed ancestors in the northwestern area of Vermont in the Lake

St. Francis/ Sokokl Band of Vermont Abenakis:

Proposed Finding - Summary Under the Criteria

Page 23

Champlain region. There is no available evidence to show there was a group identified by any of those names or other names from 1900 to 1975.To explain the lack of identifications before 1976; the petitioner argued that "Abenaki families living in northwestern Vermont after 1800 were "only rarely ... identified as Indians or aborigines, except by their closest neighbors, the same people who...either stigmatized or ignored them." In addition, official records since 1800 "usually supported the widespread view that all Indians left Vermont after 1800" (SSA 1982. 10.00 Petition, 145). As the below analysis shows, the petitioner submitted few primary documents to establish that it meets criterion 83.7(a) for the period from 1900 to 1975.

State of Vermont 's Comments

The State asserted the following:

The evidence presented by the petitioner is totally insufficient to satisfy Criterion (a). The additional evidence presented in the State's Response to the Petition contradicts the petitioner's contention that it existed as an Indian entity from 1800 to 1976, or even 1981. The numerous examples of scholars who searched but did not discover this Indian entity weighs [sic] heavily against the petitioner's claims. It stretches credulity to believe that the petitioner existed as a tribe when Frank Speck, A. Irving Hallowell, Gladys Tantaquidgeon, Gordon Day, John Huden, and Alfred Tamarin were unaware of them. For the seventy-five year period between 1900 and 1976, there are simply no external observations of an Indian entity in northwestern Vermont—or anywhere in Vermont. (VER 2002.12.002003.01.00 [Response], 119-120) (15.)

To support its argument, the State submitted most of the evidence from 1900 to 1975 examined for this criterion. The remainder of the evidence came from the OFA administrative correspondence file or the Department library.

Summary Analysis of Evidence for Criterion 83.7(a), 1900 to 1975

The types of evidence described by the regulations at section 83.7(a)(1-7) for meeting criterion 83.7(a) include repeated identifications of the group as an Indian entity by Federal, State, or local authorities, or by scholars, newspapers, or historical tribes, or national Indian organizations. The following does not summarize every document submitted. Instead, it introduces the major forms of evidence demonstrating where the petitioner does and does not meet the criterion. The following analysis demonstrates external observers did not identify the petitioning group as an Indian entity in the available evidence from 1900 to 1975.

FOOTNOTES:

15. See FAIR Image File ID VER-PFD-V0-08-D00-04.

St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of Vermont Abenakis:

Proposed Finding- Summary Under the Criteria

Page 24

Federal AuthoritiesThe petitioner did not submit any records generated by Federal sources. The State submitted all the Federal documents in the record for 1900 to 1975 evaluated for this proposed finding, none of which identified the petitioner as an American Indian entity. These included the population schedules of the Federal decennial census for three cities in Franklin County, in northwestern Vermont: Swanton and Highgate in 1900, and St. Albans in 1910. Franklin County is the claimed historical center of the petitioner's claimed ancestors. Census enumerators did not identify the petitioning group as an American Indian entity in Swanton or Highgate in the pages of the census provided. Instead, they identified individuals, all of whom were listed as "white" in the racial category (1900 Census Swanton, Vermont; 1900 Census Highgate, Vermont). They did not identify an Indian entity for St. Albans, where almost all the residents were reported as "white." The pages provided from the St. Albans census, the enumerator may have recorded four individuals from one family as "Indian," but the surnames are illegible (1910 Census St. Albans, Vermont). Identifications of an individual or individuals as having Indian ancestry do not constitute external identifications of an American Indian entity.

The State also supplied portions of Federal decennial census reports for Vermont from 1900 to 1970 (16. ). These census records furnished only the total number of people listed as "white," "Negro," and "Indian" by county. The statistics for those listed as Indian did not include tribal affiliations or specific Indian entities. As late as 1970, the census documented only 229 Indians in Vermont. It recorded 3 Indians in Addison County; 9 in Bennington; 7 in Caledonia; 46 in Chittenden; 3 in Essex; 9 in Franklin (the petitioning group's claimed historical center); 1 in Grand Isle; 14 in Lamoille; 5 in Orange; 5 in Orleans; 26 in Rutland; 26 in Washington; 36111 Windham; and 39 in Windsor (US Census Bureau 1973.01 .00) (17.)

The State provided 26 World War I draft registration forms for individuals claimed as ancestors by some petitioning group members. All the registrants identified themselves as "white," without comment by the registrar (US Military 2002.12.00). While these documents do provide some genealogical and biographical information about some of the group's claimed ancestors, they were not external identifications of those ancestors as an American Indian entity from 1917 to 1918.

FOOTNOTES:

16. See US Census Bureau 1901, US Census Bureau 1922; US Census Bureau 1932; US Census Bureau 1943; US Census Bureau 1952; US Census Bureau 1960; US Census Bureau 1973.01.00.

17. In 1980, the number of Indians recorded on the census expanded significantly. The census counted 984 Indians; 164 in the town of Burlington; 20 in Addison County; 38 in Bennington County; 16 in Caledonia County; 156 in Chittenden County, 7 in Essex County, 422 in Franklin County (183 in Swanton, and 91 in Highgate); 25 in Grand Isle County; 15 in Lamoille County; 29 in Orange County; 22 in Orleans County; 59 in Rutland County; 107 in Washington County; 91 in Windham County; 67 in Windsor County (US Census Bureau 1982.08.00). By 1990 about 1600 people identified themselves as Indian, with 585 in Franklin County. The number of Indians for other counties was: Addison, 77; Bennington, 54; Caledonia, 100; Chittenden, 294; Essex, 18; Grande Isle, total illegible; La Moille, 48; Orange, 67, Orleans, 56; Rutland, 70, Washington, 106, Windham, 74, and Windsor, 124 (US Census Bureau 1992.06.00). During this period, the petitioning group claimed about 2,200 members, mainly in Franklin County. The 1980 and 1990 census decennial reports listed only the number of Indians reported in Vermont and did not identify any Indian entities in the state.

St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of Vermont Abenakis:

Proposed Finding - Summary Under the Criteria

Page 25

Also included in the State submission were five pages of the 1937 guide to Vermont by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The pages provided some details about the ethnic composition of Vermont's population at that time. They described several ethnic groups, with French-Canadians being the largest, but did not identify the petitioning group as an American Indian entity or any Indian entity in Vermont (WPA 1937, 51-52). One page mentioned an unidentified Indian "chieftain" in Bellows Falls, Vermont (120 miles southwest of the petitioning group's claimed historical center), described as the "last Abnaki [sic] seen" in the town, who in 1856 came to the area to die, and was later buried in an unmarked grave (WPA 1937, 84). This reference to the past was not to an antecedent of the petitioning group, and clearly did not identify this unidentified identify any group after the unidentified alleged Indian's death.

The State provided excerpts from Gladys Tantaquidgeon's 1934 study of New England Indians, produced for the Office of Indian Affairs. A few pages offered a historical overview of various New England Indian groups. In portraying the social status of all these entities, the author reported "nearly 3,000 Indian descendants in the surviving bands in the New England area." Regarding the "the northern portion of the New England area, among the Wabanaki (18.) peoples, there has been a strong infusion of French blood since early times, and also some English, Scotch, and Irish" (Tantaquidgeon 1934, 4). She stated the "surviving bands" of "Wabanaki" were "the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Malecite [Maliseet], and the neighboring Micmac in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia" (Tantaquidgeon 1934, 2). Tantaquidgeon supplied a table of population figures for several mainly rural New England Indian groups, large and small, in states outside of Vermont, including the Penobscots and the Passamaquoddies of Maine, but she did not identify the petitioning group's claimed ancestors as part of any of these groups, or as an American Indian entity in Vermont or elsewhere.

The State submitted a partial chronology written in 1941 by Roaldus Richmond, supervisor of the WPA's Vermont Writers Project. Richmond included it in a February 1941 letter to Professor Arthur W. Peach of Norwich University in Vermont. The chronology, covering 1609 to 1860, was originally intended for a State Fact Book, but Richmond urged Peach to use it as a pamphlet for the Vermont Historical Society's Sesquicentennial. For 1856, the chronology noted: "Last native Indians in State leave Bellows Falls for Canada, November" (Richmond 1941.02. 10 and Richmond 1941.02. 10 Chronology, 17). The author cited no reference for this claim. While the chronology did provide some limited historical information about unidentified Indians leaving Vermont in 1856, it did not identify the petitioning group as an American Indian entity in 1941 or at any other time in the 20th century.

Relationships with State Governments

The petition record contains several documents from 1927 to 1944, almost all of which were submitted by the State, related to the Eugenics Survey of Vermont 19 (Survey or VES). This project was sponsored in the 1920's and 1930's by the University of Vermont with backing from

FOOTNOTES:18. "Wabanaki" refers to the Wabanaki Confederacy, a political alliance formed in the middle 18th century of several northeastern Algonquian tribes including the Micmac, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot, none of which were Western Abenaki. Sometimes it was also an older term used in place of Abenaki.

19. See Criterion 83.7(b) for more details on the Eugenics Survey.

St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of Vermont Abenaki:

Proposed Finding - Summary Under the Criteria

Page 26

State officials, including the Governor. (20.) These records are analyzed here because the petitioner claims the Survey targeted some of its members' ancestors due to their Western Abenaki ancestry, suggesting the possibility that the claimed ancestors may have been identified as part of an Indian entity within some of the records. (21.) One document, submitted by the State, is a three-page excerpt from the Eugenics Survey third annual report. "This excerpt discussed "some English Corruptions of French Names," and listed some English family names with their French equivalent. Survey researchers "encountered" these names "in the course of [their] investigations" (University of Vermont 1929.00.00, 4-6). The document gave only limited information about French-Canadian family names and did not identify any Indian entity.

Included in the State submissions were portions of two documents by Henry Perkins, head of the Eugenics Survey. The first was part of a leaflet of a paper Perkins originally presented as an address in 1927 to the Legislative Forum of the Vermont Conference for Social Work, in which he reviewed the project. According to Perkins, Survey researchers obtained the names of prospective subjects for the study from the State industrial school, other State institutions, and the Vermont Children's Aid Society. The chosen families, he explained, were "conspicuously detrimental in the communities" (Perkins 1927.00.00, 6). The Survey eventually selected 62 families with 4,642 individuals: To categorize them, the Survey applied various sobriquets, including "Pirates," (Jeromes, Ploof's and some Phillips') "Gypsies," (Phillips and Way's) and "Chorea" (LaCroix dit Cross's). The "Pirate" group contained mainly poor families living near rivers or Lake Champlain (these families lived on Lac Champlain and the major rivers, as "Boat People"). The "Gypsy" group migrated in the State during the summer and fall selling baskets and other wares (these were the Phillips family going from "The Plains" in South Burlington, VT to Burlington, through the Bay in Colchester, then they would hook up to Route 15, over to "Paradise Alley" or what was "Gypsy Devil Jake Way's" home in West Danville-North Peacham, along the west side of Keiser Pond in Vermont...all the way to Belfast, Maine) . In the winter, they lived in rural areas, usually relocating annually. In the case of the "Chorea" group, it supposedly had a large number of individuals with mental illnesses or nervous disorders (Perkins 1927.00.00, 7-9). It further categorized 766 as paupers, 380 as "feeble minded," 119 as in prison or having criminal records, 73 as illegitimate, 202 as "sex offenders," (such as the Sweetser baksetmaking family, the Way's and the Woodward's as well) and 45 as having some severe physical "defect," such as "blindness" or "paralysis." None of the families was categorized by race or ethnicity (Perkins 1927.00.00, 10-11). While this report reveals the methodology of the Eugenics Survey, and how it went about selecting and categorizing its subjects, nothing in it demonstrates the project identified or dealt with an Indian entity.

The second Perkins document was part of a 1930 booklet entitled Hereditary Factors in Rural Communities. It was a reprint of an article that had appeared earlier that year in Eugenics, a publication of the American Eugenics Society. Perkins also presented it at the Society's 1930 annual meeting. Perkins asserted the Eugenics Survey started in 1925, as an "outgrowth of [his] course in heredity at the University of Vermont." A by-product of the Survey was the Vermont Commission on Country Life established two years later (Perkins 1930, 1). Perkins declared the Commission wished to examine the motives of those Vermonters leaving the rural villages and the more recent immigrants and their children taking their place (Perkins 1930, 2-3). He

FOOTNOTES:

20. Strictly speaking, many of the petition documents related to the Vermont Eugenics Survey were not official State government records. The Survey, however, operated out of the University of Vermont, a State institution, and had the backing and involvement of important State officials and agencies. For example, the names of prospective subjects for the Survey were obtained from the State industrial schools or welfare agencies which had contact with such individuals. Most importantly, the Survey's findings played a prominent role in the State's social welfare policies in the 1930's, including a "voluntary" sterilization program. For these reasons, the Survey materials are identified here as State-related documents.

21. See, for example, SSA 1995.12.11 [Second Addendum], 4, 9.

St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of Vermont Abenaki:

Proposed Finding - Summary Under the Criteria

Page 27

indicated that the State's "largest single foreign element" was "French-Canadian." Smaller groups included the Scots, Italians, Welsh, Poles, and Russians, but Perkins but did not refer to any Indian group (Perkins 1930, 1-2). The Commission intended to study a "dozen or more towns," and had already researched some "key families" in rural areas for more than a year (Perkins 1930, 4-5). While this article revealed the methodology behind the Eugenics Survey, nothing in it shows the project identified or dealt with any Indian group.The petition record contains eight unnumbered pages of a Eugenics Survey "Pedigree" file compiled around 1927 to 1930 for a prominent claimed ancestral family of some petitioning group's members. (22.) All but one page provided limited biographical information on six family members, including name, source of information for the subject, spouse's name, nationality, personality characteristics, date of birth or death, and names of children. All these individuals except for one were identified as French in nationality, and that person was listed as Irish. No one was identified as having Indian ancestry or as being part of an Indian community (Pedigree SF 1927-1930).

One of the pages submitted, containing only two short paragraphs, did not discuss any family members, but stated that a high school principal, Mr. Barton, from Essex Junction, Vermont, was a good source of information about "families in Swanton."

The document stated as follows:

Mr. Barton says that Back Bay, Swanton, was settled by the French when they thought they were settling in Canada. The result is a French and Indian mixture. He says the St. Francis Indians are a French and Indian mixture.

The principal, as paraphrased here, appeared to be giving his opinion of how he believed Swanton was originally settled by non-Indians, and how that might have contributed to the contemporary racial and ethnic makeup of the section of the town rather than identifying a contemporary Indian group in Swanton. (23.) The principal's comment on the St. Francis Indians was most likely a reference to the historical tribe at Odanak, Quebec, known by that name since the colonial period, rather than a contemporary Indian entity in Swanton. Although the petitioner goes by the name "St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of the Abenaki Nation of Vermont," a reference to the St. Francis tribe or Indians of Canada in a 20th century document, is not a reference to the petitioning group or its claimed ancestors. It must also be remembered that none of the individuals in this file was identified by the Eugenics Survey as Indian. The principal did not identify the petitioning group's claimed ancestors as part of an Indian entity in Swanton for 1927 to 1930.

The State provided some pages containing mostly biographical information relating to another family from the Eugenics Survey files, apparently compiled about 1930 (Eugenics Survey of Vermont 1930, npn). Some petitioner members claim to be descended from the family mentioned in these documents. The biographical information, consisting of 10 unnumbered

FOOTNOTES:

22. The State submitted six pages; the petitioner submitted two.

23. The principal's opinion was historically incorrect. In fact, many of the original, permanent non-Indian settlers of Swanton in the late 1780's and 1790's, were not French from Canada, but English and Dutch settlers from the United States. French-Canadians began migrating to the Swanton area in significant numbers during the middle of the 19th century.

St. Francis/Sokoki Band of Vermont Abenakis:

Proposed Finding– Summary Under the Criteria

Page 28

pages for a few of the ancestral members of this family, came from the notes of the Survey interviewer (Harriett E. Abbott). While a few individuals claimed some Indian ancestry, the Survey did not identify any "tribal" entity to which they belonged or indicate they were part of a contemporary Indian entity. One family member mentioned her great-grandmother was an Indian from St. Regis, New York (Akwesasne), and one male member reported being part Kickapoo. Another female member, who had married into the family, claimed to be from Caughnawaga (Kahnawà:ke), indicating likely Iroquois (or Mohawk) rather than Western Abenaki ancestry. The pages from this file identified other families married into the line as partially of Indian descent, but did not specify any Indian entity. It also contained five pages of information about several small towns in northwestern Vermont, including Grand Isle and Swanton, suggested for possibly being part of the study (Eugenics Survey of Vermont 1930). But the file offered no discussion of an Indian entity in these towns; rather it affirmed most of these towns were predominantly French-Canadian. This document did not identify the petitioning group's claimed ancestors as an American Indian entity.The State submitted portions of the first few chapters and the appendices from a 1937 book by Elin Anderson called We Americans, based on a Eugenics Survey project. It was a "sociological" study of ethnic groups in Burlington (Anderson 1937, 8). This study found that 40 percent of Burlington's population was either immigrants or their children. French-Canadians were the largest ethnic group, being half of all the first- and second-generation ethnics, and one-fifth of the city's population. Other ethnic groups in descending order by number were English-. Canadian., Irish, Russian and Polish (these two groups classified as mostly Jewish), English, Italian, German, and 29 other nationalities. Two-thirds of the city's population derived from these newer ethnic groups (Anderson 1937, 17-18). The remaining populace was "Yankee" or fourth-generation "kindred ethnic stocks," defined as English, English-Canadians, or Germans of Protestant faith (Anderson 1937, 19). The study did not, however, describe or identify any Indian entity containing the petitioner's claimed ancestors in the community.

The State also offered excerpts from Lillian Ainsworth's article entitled "Vermont Studies in Mental Deficiency," which appeared in the 1944 issue of Vermont Social Welfare. Ainsworth, a former journalist, poet, and editor of Vermont Social Welfare, served for several years as secretary to the Commissioner of the State Department of Public Welfare before her death in 1946. The article described the history of the Eugenics Survey from its inception in 1925 to its conclusion six years later (Ainsworth ca. 1944). Ainsworth provided some information about the methodology employed in the Burlington study and how it surveyed certain ethnic groups, but she did not identify the petitioning group's claimed ancestors as part of an Indian entity considered for examination.

Dealings with County, Parish, or other Local Governments

The State submitted approximately three dozen birth certificates dated 1904 to 1920 from Swanton, Vermont, belonging to some of the petitioning group's claimed ancestors. The petitioner contends the records are significant because in some cases individuals appear to be listed as "Indian-White." But the racial designations are ambiguous, as described in more detail in criterion 83.7(b). In no case did the record keeper identify any of these individuals as belonging to a specific Indian group (Birth Certificates [BC] 1904-1920). And even if he or she had correctly identified Indian ancestry for the child, the identification of all individual as having

St. Francis/Sokoki Band of Vermont Abenakis:

Proposed Finding– Summary Under the Criteria

Page 29

Indian ancestry does not constitute an identification of an Indian entity. To be acceptable evidence for criterion 83.7(a), an Indian group must be identified, not just an individual.Anthropologists, Historians, and/or other Scholars

In 1907, the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of American Ethnology published the Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Part I, edited by Frederick W. Hodge. The State provided a section of the book dealing with the Abenaki. The study described the historical Abenaki as being mostly from Maine. It asserted that since 1749, "the different [Abenaki] tribes" had "gradually dwindled into insignificance." The remaining descendants "of those who emigrated from Maine, together with remnants of other New England tribes," were "now at St. Francis and Becancour, in Quebec, where under the name of Abenaki, they numbered 395 in 1903" (Hodge 1907, 3-4). This identification of the Indians at St. Francis and Becancour in Quebec, Canada, is not an identification of the petitioner, whose claimed ancestors lived almost entirely in northwestern Vermont at that time. The book provided the populations of the Penobscots and Passamaquoddies of Maine, neither of which are Western Abenaki (Hodge 1907, 4). Regarding the historical Missisquoi ("Missiassik") Indians of Vermont, from which the petitioner claims to have descended, the book portrayed them as "formerly living" in a village on Vermont's Missisquoi River. According to Hodge, this village had been abandoned around 1730. He did not identify a contemporary group living in this area (Hodge 1907, 872). This selection did not identify the petitioning group as an Indian entity in 1907.

The State furnished excerpts from Warren K. Moorehead's American Indian in the United States, Period 1850-1914. When the book was published in 1914, Moorehead was curator for the Department of American Archaeology at Phillips Academy in Massachusetts and a member of the U.S. Board of Indian Commissioners. Moorhead described the present condition of northeast Indians. For New England, he discussed only the Penobscots and Passamaquoddies of Maine, neither of which are Western Abenakis or the claimed ancestors of the petitioner (Moorehead 1914.00.00, 32-35). The book did not identify the petitioning group as an Indian entity in 1914.

The State supplied a copy of the 1926 article, "Culture Problems in Northeastern North America," by anthropologist Frank Speck, which appeared in the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. Speck spent considerable time, including field work, studying Abenaki groups in Maine and Canada during his career. He described the article as a "survey" of the "cultural properties" of Indians in northeastern North America. Speck also discussed in broad cultural terms the "Wabanaki group south of the St. Lawrence." In this region were "the members of the "Wabanaki" group, beginning with the Pigwacket of New Hampshire, extending eastward and embracing the Sakoki, (24.) Aroosaguntacook and Norridgewock, and the better known Wawenock, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Malecite and Micmac, with an approximate native population of some 6,000" (Speck 1926.04.23, 272, 282). As described here by Speck, none of these groups was in the Lake Champlain region of Vermont, which is the claimed geographical center of the petitioning group. Most of the analysis Speck provided focused on the Eastern Abenakis of Labrador or Maine and their aboriginal antecedents, with extensive reliance

FOOTNOTES:

24. Before Gordon Day cleared up the confusion in the late 1970's, many historians and anthropologists mistakenly identified with the Saco River Indians of Maine, who were Eastern Abenakis, with the Sokoki Indians of the upper Connecticut River, who were Western Abenaki (Day 1978a, 148).

St. Francis/Sokoki Band of Vermont Abenakis:

Proposed Finding - Summary Under the Criteria

Page 30

on archeological evidence (Speck 1926.04.23, 282-292). He did not identify the petitioning group's claimed ancestors as part of a contemporary Indian entity in Vermont or elsewhere 1926.The State included a copy of Irving Hallowell's 1926 article, "Recent Changes in the Kinship Terminology of the St. Francis Abenaki," published in the Proceedings of the International Congress of Americanists. The work was mainly a linguistic study of those St. Francis Indians in Quebec. Hallowell, an expert on Algonquian tribes, assessed changes in kinship terminology among the "St. Francis Abenaki tribe during the past two centuries" (Hallowell 1928, 98). These St. Francis Indians were not the claimed ancestors of the petitioner in northwestern Vermont in 1928. Hallowell described them as the Indians who had "occupied a reservation oil the St. Francis River (P. Q., Canada), about sixty miles east of Montreal since the end of the 17th century, although their ancestral home was in New England." In his view, these were the "native peoples who formerly occupied the lower Kennebec (Canibas or Norridgewocks, and Wawenock) and the Valley of the Androscoggin (Arosaguntecook) Rivers in Maine with at least some additions from the region of Saco (Sokokis) and Merrimac (Pennacooks) in New Hampshire" (Hallowell 1928, 98-99). While Hallowell discussed some historical groups in Maine and Vermont, and the contemporary St. Francis Indians of Quebec, he did not identify the petitioning group's claimed ancestors as part of an American Indian entity in Vermont or elsewhere in 1926.

In 1948, the Library of Congress published William Harlen Gilbert Jr.'s, Surviving Indian Groups of the Eastern United States, an excerpt of which the State furnished. Gilbert provided the population of many New England Indian groups, none of which identified the petitioning group. For Maine, he supplied the following totals: 76 "Malecites" [Maliseets] in Aroostook County on the "northern border," 444 Passamaquoddies in Washington County on the "eastern border," and 354 Penobscots in the county of the same name in Central Maine. None of these groups are Western Abenaki. He did not note any "surviving social groups of Indians" for either New Hampshire or Vermont. Instead, he asserted New Hampshire had only a "few Pennacook Indians near Manchester,"and Vermont a "few scattered Indians" on the census records (Gilbert 1948, 407, 409).

The State also submitted portions of journal notes from Gordon Day, a leading expert on the historical Western Abenaki. Day engaged in extensive study of the Western Abenaki from the late 1940's to his death in 1993. He kept this journal from 1948 to 1962, while doing field work among the St. Francis Indians of Quebec, Canada. Throughout the journal, Day recorded his visits to various Indians and Indian groups, mainly Western Abenaki from Canada. In August 1951, Day recorded his visit to "Chief Wawa's" camp in Keene, New York, operated by an Odanak Indian named Henry Wawanolett, indicating that early on he was attempting to visit Indians in the United States as well as at the St. Francis reservation in Quebec (Day 1948.07.001962.11.13, 1). He also mentioned members of the Obomsawin family, Western Abenaki informants connected to the Saint Francis reservation in Quebec, then living at Thompson's Point on Lake Champlain in Charlotte, Vermont. On July 28, 1957, Marion Obomsawin (b.1883) and her sister Elvine Obomsawin Royce (b. 1886) informed Day their father originally came from Odanak and migrated to Vermont between 1895 and 1900 (Day 1948.07.00-1962.11.13,1-2,9,13-14).