Page [60.]

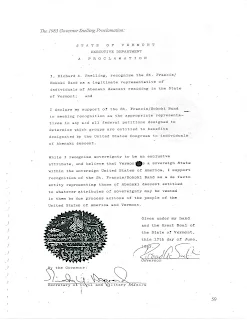

In the 1980s the Missisquoi Abenaki exerted their autonomy and aboriginal rights to fish without a license in the State of Vermont by conducting a series of fish-in demonstrations to draw attention to their situation and force the state to recognize their presence and continued existence in their ancestral homeland. The state filed charges against Chief Homer St. Francis and other Missisquoi citizens and brought them to district court with Judge Wolchik presiding. Below are excerpts of the court's Findings of Fact which upheld Missisquoi's inherent right as a Native American tribe to fish without a license.STATE OF VERMONT

FRANKLIN COUNTY, SS.

VERMONT DISTRICT COURT

FRANKLIN CIRCUIT, UNIT #2

STATE OF VERMONT DOCKET NO. 1171-10-86Fcr

1327-11-86Fcr

V. 15-1-87Fcr

HAROLD ST. ERANCIS

STATE OF VERMONT DOCKET NO. 703-5-88Fcr

752-6-87Fcr

V. 771-6-87Fcr

1023-8-87Fcr

JOHN CHURCHILL 1045-8-87Fcr

STATE OF VERMONT DOCKET NO. 937-7-88Fcr

V.

HOMER ST. FRANCIS

STATE OF VERMONT DOCKET NO. (Fishing Without License)

V.

HOMER ST. FRANCIS

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

NOT INCLUDED IN THE APPLICATION

Introduction

Defendants' in their cases consolidated for hearing on Motions to Dismiss, ask for dismissal because of superceding, ancient, tribal rights and/or for lack of jurisdiction. The bulk of these defendants are charged with either fishing without a licence or failing to show a license upon the request of a game warden. These Defendants seek dismissal on the ground that there has been no extinguishment of their alleged aboriginal right as members of the Missisquoi Abenaki tribe to fish in their aboriginal homeland. These same defendants join with the remaining defendants, who are charged with various crimes claiming that the site of each charge is in "Indian Country" and, therefor, is not subject to state criminal jurisdiction.*

For the reasons set out below this court dismisses the charges against all but six (ftnt. 1) of the so-called "fish-in" defendants because it recognizes their claims to extinguished aboriginal fishing rights. The court does not find that any of the charges occurred in Indian Country and does not dismiss any on that ground.

__________

* Due to technical difficulties the court will designate footnotes in the text by "ftnt" or "Ftnt." depending on placement.

Ftnt. 1. There is insufficient evidence to find that Sylvia Wells, Tammy Lee Conger, Richard Rowe, Mark Rushlow, Raleigh Elliot or Joy Mashtare are members of the Missisquoi Abenaki tribe with Missisquoi Abenaki Ancestry.

NOT INCLUDED IN APPLICATION REVIEW

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

The application of the "ultimate legal issue" standard discussed in Riess v. A.O. Smith Corporation, No. 87-012 (Vt. Nov 10, 1988) was left open at the close of the evidence for study by the court. The court concludes that where the Riess objection was made the expert witness was not testifying about the ultimate legal issue before the court. Even if the testimony was on such issue there is sufficient supporting testimony, tested by cross-examination,, to support the findings made by the court without dependence on such testimony.

The court admitted Defendant's Exhibit U, an unsigned proclamation. The court now concludes that the document is irrelevant and excludes it.

The court initially excluded as irrelevant the State's Exhibit# 22 submitted in connection to the deposition of Dr. C. Calloway, An with the Act Regulating Fisheries, March 8th, 1787. 1787 Vt. Laws at 253. After further review the court concludes that the Act has some relevance and now admits the exhibit.

In the conclusions of law references to findings of fact are desginated "FF."

Acknowledgement

The undersigned Judge: wishes to thank Susan Gilfillan, Esq., without whose scholarship, patience, energy and flexibility this decision would still be in its preliminary stages.Page [61.]

FINDINGS OF FACT

The facts found below are a distillate of six days of trial testimony of lay witnesses, police officers and experts in anthropology and ethnology (ftnt. 2) and the deposition testimony admitted by stipulation of two experts in ethnology. All expert testimony is that of the defense; the State called only police officers. A large number and variety of exhibits, including maps and ancient documents, added valuable information. Neither here nor in the conclusions of law do we try to resolve the unresolvable questions, e.g. whether the Republic of Vermont ever was an independent nation. Those we leave for other tribunals at other times.All found facts are anchored in particular testimony or exhibits. For the convenience of the close reader we provide source notes for virtually all of them, which translate as follows: T II at 12 means Volume II of the trial transcript at page 12; D at 11 beans the Gordon Day deposition at page 11; C I at 6 means Volume I of the Colin Calloway deposition,

________

Ftnt. 2. Ethnology is a branch of anthropology concerned with the different branches of the human race. D at 11 at page 6.

Page [62.]

A. Missisquoi Abenakis A continuing native American presence since time immemorial.

1. Over the last several decades researchers have recovered and literally unearthed documents and artifacts that have changed how even serious students of ethnology look at Vermont's native American population. For the longest time the most widely held opinion was that Indians never lived in Vermont, but new information has changed that notion. C III at 37, T 1132-133.2. Historically, the Missisquoi Abenakis (Missisquois) are a group of Western Abenakis. D at 23.

3. The Missisquoi are one of several Western Abenaki tribes. The others include the St. Francis at Odanak, Quebec and the Penacooks of New Hampshire.

4. Western Abenakis inhabited primarily Vermont, New Hampshire, southern Quebec and western Maine. T I at 108.

5. The Eastern Abenaki, who inhabit a large part of Maine, differ primarily for the Western Abenaki linguistically. T I at 122.

6. Archaeologists have traced an essentially unbroken chain of evidence documenting Missisquoi presence in northwestern Vermont, back to 9300 B.C. They have found and examined extensive village sites, habitation and campsites and cemeteries. T I at 123-124.

7. Archaeological evidence exists that demonstrates the Missisquoi were farming in this homeland in the river flood plains at least as far back as 1123 A.D. T I at 163-164.

8. Up until first European contact no other tribe ever used, inhabited or otherwise occupied the Missisquoi homeland; the Missisquois had exclusive control and dominion over the area. T I at 124, T IV at

Page [63.]

30-31, D at 124-126 and C III at 53.

9. Other evidence, some of which is explored in more detail below, bolsters the archeological record. Place names have a Missisquoi source. The river that flows through the region is the Missisquoi. It flows into the Missisquoi Bay. "Missisquoi" is derived from the Western Abenaki "Mazipkoikis", meaning "place where there is flint." Oral traditions, stories carefully handed down from generation to generation place Missisquoi origins in northwestern Vermont. When given an opportunity the Missisquoi have consistently insisted upon their continued presence essentially forever. T I at 149.10. In nonliterate societies oral traditions allow exploration of all levels of society. Written histories tend to focus merely on the concerns of the literate upper levels. Experience with oral histories demonstrates that they are just as reliable as written histories. T I. at 127 and 130. Accuracy of reporting can be maintained over extraordinary periods of time. T I at 128.

11. The Western Abenaki, including the Missisquoi, have a very definite, carefully maintained, carefully transmitted oral tradition, which is a useful source of information concerning the location of their ancestral homelands. D at 47-49.

12. By way of example, the Western Abenaki set their stories of creation and transformation in the Champlain Valley of Northwestern Vermont. In the creation and shaping of the earth the last element completed was Lake Champlain. Odziozo, the principal transformer, turned himself into stone so that he could watch for all eternity his finest creation, Lake Champlain. T I at 150 and D at 61.

13. These traditional stories of the early beginnings imply a

Page [64.]

long standing presence of Western Abenaki culture in northwestern Vermont. T I at 152.

14. In 1609 Samuel Champlain, when exploring the lake named after him, became aware of the presence of the Missisquoi, people residing in northwestern Vermont, whose ancestors had lived in that part of what is now known as the United States and whose tribe or comnunity recognized them as Indians. T I at 148.15. In 1615 French missionaries observed established Missisquoi settlements settlements, including a village on the lower falls of the Missisquoi River, a group in St. Albans and a separate group on the Lamoille River. T I at 149 and T III at 112.

16. From the time of Champlain's explorations to the formal transfer of power to the British after the French defeat in the French and Indian wars (1609-1763) despite French presence and influence the Missisquoi remained in place as a distinct native American community. C III at 58.

17. Because the French depended upon the native Americans as, allies their policy was to pursue and maintain harmonious relations with them. C III at 56.

18. In 1635 Western Abenakis first appeared in history as a "distinct ethnic group," making contact with Europeans at Penacook or Concord, New Hampshire and Northfield, Massachusetts. D at 44.

19. The first specific historical references to Abenakis as a "distinct ethnic group" located on the eastern shore of Lake Champlain were made in 1680. D at 44.

20. Among the exhibits are a series of maps which demonstrate, in part, a continued Missisquoi presence on the eastern shore of Lake

Page [65.]

Champlain. The Court accepts these and the others mentioned from time to time below as legitimate and relevant. Among these are Defendants' Exhibit C, a map published in 1694. This map is the first printed view of the Lake Champlain watershed with many of the same place names we have today, e.g. Missisquoi (the village), Winooski and Otter Creek. T III at 179.

21. In 1723 written reference to Missisquoi as a geographical location appears because of the attacks of "Grey Lock, a Missisquoi war leader, who directed his efforts for the most part against the frontiers of Massachusetts. D at 45, 59, and 110; C III at 65.22. Grey Lock's belligerence during the period 1700-1740 established Missisquoi in the minds of the English as a bastion of Abenaki resistance and brought the pace of British settlement to a screeching halt. C III at 66-67, T III at 189-190.

23. In 1730 a plague hit the Missisquoi area, which the inhabitants temporarily abandoned in favor of Odanak, Quebec. They returned by 1732. D at 139.

24. In the short period that followed quite a few Western Abenaki came from Odanak and settled in Missisquoi, which was a substantial village in 1738. D at 140.

25. During the 1730's-1740's the Missisquoi were coming to Fort Frederick, a French mission base across the lake in New York, to visit, be baptized or engage in other religious activity. Their names show up on the fort's baptismal records. C I at 53-54.

26. Defendants' Exhibit G is a map of New England and New France, published in 1749, showing Mississiasi (Missisquoi) at Missisquoi Bay.

27. In 1759 with the French and Indian war raging around it the

Page [66.]

Missisquoi community remained intact. T III at 213.

28. Defendants' Exhibit L. an English military map, shows the location of the Missisquoi village in 1762. T III at 226.29. In 1765 a Canadian merchant, James Robertson, negotiated a ninety-one year lease of land with the heads of nineteen Missisquoi families. The property was located on the lower Missisquoi River and encompassed most of what we now know as the village of Swanton and all land down to the mouth of the Missisquoi river. T III at 221 and D at 138.

30. The alleged fishing violations of thirty-one of the defendants occurred within the boundaries of the lease. T III at 221.

31. Missisquoi culture did not countenance individual ownership of real property; the Missisquoi held their homeland collectively. As a result, the heads of family bands, which could comprise as much as fifty individuals each, signed on behalf of their bands.. T III at 220, C III at 87 and 89-90.

32. The lease by being a lease and not a sale, theoretically guaranteeing a reversion, demonstrates an effort by the Missisquoi to grapple with European settlement in a way that ensures long term sovereignty over the entire area. T III at 217.

33. Some of the Missisquoi who signed the lease used French baptismal names. When dealing with Europeans this practice was very common simply because it was easier. D at 172.

34. By it terms the lease demonstrates that the Missisquoi were planting and harvesting crops during the 1760's.

35. Grand Avenue and South River Streets, where some of the crimes alleged in the informations underlying the pending motions to dismiss

Page [67.]

allegedly occurred, are in the village of Swanton within the land encompassed by Robertson's lease. T IV at 153.

36. When the Treaty of Paris in 1763 ended the French and Indian war the Missisquoi suddenly found that they were included under the authority of the governor of New York, rather than of Canada, with whom they had been allied and Upon whom they depended for trade and supplies. D at 92-93.37. La Motte, one of the Lake Champlain Islands that is a part of present day Grand Isle County, the governor of Quebec, Governor Murray, and the governor of New York, Governor Moore, met primarily to establish the forty-fifth parallel as the boundary between the two English territories. C II at 37, C III at 95, D at 92-93. Also present at the meeting was Daniel Claus, a deputy of the English Indian Affairs Office. C II at 37. The Missisquoi and the Caughnawaugas, a Catholic Mohawk tribe that was part of the Iroquois nation, sent representatives to the Isle La Motte meeting. C III at 97-98.

38. At the meeting, the Missisquoi complained of settlers on their land. C II at 56. The Caughnawauga claimed the Missisquoi territory on the basis that they were the descendants of ancient Mohawks who frequented the area. C I, Ex. F. XII Papers of Sir William Johnson 172 (M. Hamilton ed. 1957) "An Indian Conference"; C III at 95-96. Apparently in protest to the Caughnawaugas' claims to the territory, the Missisquoi claimed that they had controlled the Missisquoi territory "for time unknown to anyone here present" and no one else had laid claim to it with the exception of the French who requested to erect a sawmill. Hamilton, supra; C III at 100. The

Page [68.]

Caughnawaugas' then released their unsubstantiated claim to the territory, retaining only hunting and fishing rights. C II at 37-38, C II at 95-6, T III at. 77 at D at 96. There is some evidence that Daniel Clause considered the Caughnawaugas' cession to operate as a cession of Native American possessory rights in the Missisquoi territory. C. II 38, 111; C IV at 184.

39. The British did not have the overwhelming archaeological evidence available to us today to know that the Caughnawauga claim was unsupportable. There is no reason to believe they had any evidence to support the Caughnawauga position, either. In any case, the British took a most convenient position, that the Caughnawauga concession was something in their power to make. C II at 37-38, C II at 96.40. Defendant's Exhibit M consists of two maps published in 1776, each noting the position of the Missisquoi village. T III at 228..

41. In the period 1775-1785 the Missisquoi lost control of choice farmland along the Missisquoi River as English and Dutch settlers moved in. D. at 87.

42. A letter from Clement Gosselin to Ira Allen substantiates the presence of Missisquoi in the Missisquoi homeland in 1786. They were claiming land and threatening to use force against the settlers. C II at 101-102.

43. In 1783 the Missisquoi engaged in a traditional non-confrontational response; they went "underground." More specifically their response to the influx of Europeans was withdrawal from central areas into other areas in the Missisquoi homeland, where they would be out of sight. There is no evidence that they ever abandoned their homeland, though some did move to Odanak. When

Page [69.]

underground they never had total invisibility. C I at 77, D at 140 and 186 and C I at 78.

44. These withdrawals were generally designed for various reasons of safety, including, e.g., protection against plague outbreaks, the Revolutionary War and threats from Iroquois and Algonquin tribes.. T I at 181-182, C at 78 and D at 174.45. Following the Revolutionary War the majority of the Missisquoi stayed in the homeland.

46. After being dispossessed of lands the Missisquoi repeatedly asserted their claims to the land. D at 91.

47. British maps, oral traditions and public records confirm the continued existence of the Missisquoi community in the 1790's, though the tribe lost possession of same lands it formerly held. C III at 139-140, C I at 80.

48. In 1790 the Dutch settlers were getting along pretty well with the Missisquoi. Face to face confrontations with yankees over their presence and control of land are of record. C I at 75-76.

49. Defendant's Exhibit N is a map published in 1791, showing an Indian "castle." This term is misleading. It means a village, perhaps one where there was a palisaded area to which the inhabitants could withdraw in case of attack. T III at 234-235, C III at 134-135, C IV at 43.

50. This village is also noted on the maps as Grey Lock's castle. Construction of whatever palisaded structure that may have existed occurred late in the seventeenth century, C IV at 43, T III. at 30.

51. Although they remained united by 1791 the Missisquoi were dispossessed of the choicest part of their homelands and were in

Page [70.]

several neighborhoods around "a particular though ill-defined territory." D at 89-90, T 1203-204.

52. Defendant's Exhibit N is a map published in 1794, which continues to show the Missisquoi in place. T III at 236-238.53. Defendant's Exhibit P is a map which shows the Missisquoi village still intact. That situation came to a final halt in 1798. From then on the Missisquoi no longer occupied their main village. T IV at 25, 33.

54. At the dawn of the ninteenth century the slow process of converting the Missisquoi into a group of family bands was complete, but the "ethoncentric historical juggernaut" that pressed for a conclusion that the Missisquoi had abandoned their homeland was fueled by fantasy C II at 189, T III at 149.

55. We know now that Western Abenaki presence in Vermont was significant at the time of European contact, that it remained significant, and that even though there is migration, movement and upheaval in their homeland there is a continuing and persistent Missisquoi presence to time present. C III at 38, T I at 156-157, T III at 203, and D at 129.

56. The Missisquoi never voluntarily abandoned any portion of their homeland. T IV at 32.

B. Fishing: Basic Native American subsistence

57. The Missisquoi homeland since time immemorial has been an "extremely good place to live." The main village was "one of the richest natural sites in the northeast." "That's why [the