The CD-ROM indexes for the 1870 and 1880 censuses disclose the names of the

families classified as Indian. The Indian families on the 1870 census include two New Jersey families—the Jacksons. The others are listed as having emigrated from Canada—indicating they are not long-standing Vermont residents. Moreover, none of these families is listed as living in Franklin County, the area of the petitioner's supposed traditional home (U.S. Bureau of the Census, Family Quest 1870).The 1880 census gives similar information. It shows four families of Indians

Jackson, Emory, Koska and Bomsawin. Only one of the heads of families was born in Vermont—the others are immigrants from Canada, Massachusetts, or New Jersey. Two of the families lived well south of Missisquoi—In Rutland and Addison Counties. The Jackson family, shown living in Essex County, was from New Jersey, and is not a native Vermont family. The last one is the Obomsawin family a well-known name in the records of Odanak/St. Francis. The Obomsawins maintained continuous contact with and membership in the Odanak Reserve. None of the families listed in the 1880 census appears on the genealogical charts submitted by the petitioner. 35. See discussion in section on Criterion

(e)—Descent From Historic Tribe.

The 1890 census was the first of three federal censuses to specifically seek out

Indians and enumerate them on special forms. In Vermont, this census listed 34 Indians. Although the individual listings of the 1890 census were destroyed in a fire, a compilation summarizing the results of the Indian census survived. This compilation shows the counties

________________

FOOTNOTE:

35. The two members of the Obomsawin extended family shown on the 1880 census are William and Mary Obomsawin. They are not included in the petitioner's Family Descencdancy Charts. The only Obomsawin alive in 1880 who is included on those genealogical Charts is Simon Obomsawin. Simon reportedly came to Vermont in the early twentieth century (Huden 1955).

in which those 34 Indians lived; none lived in Franklin County. It disclosed thirteen Indians in Essex County, quite likely the Jackson family, which showed up there in the previous census. It also listed eight in Chittenden County, eight in Windsor County—in the far-southeastern corner of Vermont—and five others scattered around the state. However, no Indians were uncovered in Franklin County (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1894:602). These census materials are consistent with the observations of the local historians and surveyors who reported no Indian communities in Vermont after 1800. The lack of any significant numbers of Indians in the federal censuses confirms the views of those local reporters that the Indians they saw were travelers visiting the state.

Sightings of Indian Visitors and the Basket Trade

So what is the explanation for these traveling Indians who were sighted in Vermont? The trade in baskets provides one answer. The St. Francis Abenakis, like Indians from other tribes, made woodsplint baskets in the winter and sold them to whites in the summer. The tradition of making twined bags for carrying things was an older aboriginal custom. The practice of making splint baskets to sell to whites was more recent, spreading from the Indians of the Delaware Valley northward in the eighteenth century (Brasser 1975:8, 20-21). When the Indians no longer were able to rely on fur trading for subsistence, they turned to making and selling baskets (Brasser 1975:15, 28). The earliest known trade in baskets in Vermont is from 1799, when a group of starving Indians from Odanak/St. Francis came down the Missisquoi to Troy, Vermont (Brasser 1975:21, 27, Sumner 1860:22, 26). The only other evidence of an early nineteenth century Indian basket made for whites is from the

1820's: a Mahican basket lined with pages from the Vermont newspaper the Rutland Herald (Ulrich 2001:352).

A few local reports of traveling families of Indians loaded with basketmaking

supplies confirm that the families seen in Vermont were part of the Canadian Indian basketmakers. One such account comes from the journal of Edwin H. Burlingame, an instructor at the Barre Academy in Barre, Vermont. He wrote of this encounter in his diary in October 1853:

Towards night Moore and myself walked about a mile above the village to an encampment of Indians who have been stopping here for a few days. We found them with their tents pitched near the river, a couple of distinct tribes, one from St. Francis in Canada, and the other from Maine. The tents were of white cotton cloth in the triangular shape and large enough to hold four or five persons comfortably. They were filled up with basket stuff and material for bows and arrows. The basket stuff was in strips, some of them dyed blue, yellow, and red, while heaps of finished baskets of all shapes and sizes were piled up in the middle. (Burlingame 1853:16).

Another similar reference to Abenakis traveling down the Connecticut River to sell their wares appears in the History of Barnet, Vermont written in 1923:

Yet within the recollection of many who are still living, small bands of the Abenaquis Indians came down the river in birchbark canoes in summer during several years. Men, women and children built wigwams In true Indian fashion, covered with bark and the skins of wild animals, bringing with them baskets and other trinkets which they had made during the winter. The men spent most of their time in fishing and hunting, while the women sold their wares from house to house. Such a company visited Newbury as late as 1857. (Wells 1923:4). 36.

One further account of Indian visitors from out of state comes from Lyman Haves, History of the Town of Rockingham in the southeastern part of Vermont.

During all the first half of the last century small parties of more civilized and peaceable Abenaqui Indians used to visit Bellows Falls nearly every summer, coming from their homes in Canada and New York state. They came down

_________________

_________________

FOOTNOTE:

36. Newbury and Barnet are located on the Vermont-New Hampshire border along the Connecticut along River (see map above, p. vi).

the Connecticut in their canoes, usually bringing supplies of baskets and other trinkets which they had manufactured during the previous winters, which they sold to citizens of Bellows Falls and the then large number of summer visitors....The last remnant of this tribe came to Bellows Falls early in the summer, about 1856, in their birchbark canoes. (Hayes 1907:48-49).

The narrative goes on to portray the old chief who came to Rockingham with his

family. It recounts stories the old man told about his war service with the English, and his visits to England. It describes the large silver medal from King George III which he wore. Most of his family returned to Canada at the end of the summer, but the old man, in ill health, stayed until he died there late that autumn. After burying him, his son returned to Canada, and no further mention of Indians in the area appears in the town history (Hayes 1907:49-50).

It is worth noting that these sightings of Indians were in parts of Vermont far from Swanton. Barnet is in the northeastern part of the state. Barre is in the central part of the state, and Bellows Falls is in the southeastern section. In two of the three accounts, the Indians are specifically identified as coming from Canada, Maine, or New York. In the third, the Indians came down the river to Barnet—which means down the Connecticut River, from the northern tip of New Hampshire, Canada, or Maine. In none were the Indians described as residing in the area. They were seasonal visitors who lived most of the year in Canada.

All the sightings above appeared before 1860. After 1860, to 1920, the Abenakis of Odanak/St. Francis made baskets for the tourist trade. They took their baskets directly to the emerging resorts and set up shops to sell their wares all summer (Pelletier 1982: 1, 5, Pierce 1977:48-49 citing conversation with Stephen Laurent; McMullen & Handsman 1987:28).

These resorts were not located in the areas of any historic Indian villages. The

baskets made during this time period were fancy baskets for wealthy tourists, they were more elaborate than the previous period's utilitarian woodsplint baskets (Ulrich 2001:347, Lester 1987:39). During this time, entire families from Odanak/St. Francis would move to a tourist

area in the United States and stay there from the spring to fall. They sold baskets that they had made during the winter (Pelletier 1982:1, 5). This was a prosperous livelihood:

Each family chose a different resort area to which they usually returned annually and where they either owned a house or rented one. A basket stand or shop was erected on the premises from which they displayed their work and demonstrated their craft....In order to make the maximum number of baskets in the summer, the women were often freed from their household responsibilities by hiring local people to do the domestic work for them (Pelletier 1982:5).

The resorts to which these families of Odanak/St. Francis traveled to set up shop included Highgate Springs, Vermont, on the border with Canada (Hume 1991:106). This Highgate resort area, along with others in the White Mountains of New Hampshire; Lake Placid, Lake George, Lake Mahopak, and Saratoga Lake, New York, Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Michigan, was chosen for its high concentration of tourists--the basket-buying customers of the Victorian age. Odanak/St. Francis Abenaki chief Joseph Laurent made a conscious effort to develop the basket selling business at such resorts by establishing seasonal Abenaki camps in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (Hume 1991:103). After over thirty years of selling baskets from this Intervals, New Hampshire, camp, the area became known as a center for Indians from Odanak despite the fact that they had no previous historical tie to the area (Hume 1991:105, 111). Two members of the Obomsawin family interviewed by Gordon Day in 1957 stated that they did not believe that Abenaki families from Odanak/St. Francis returned to their historic place of origin to sell baskets. Rather, they believed sites for selling were chosen based on the ability to make sales (Day 1948-1973:14).

The fact that the Abenakis of Odanak/St. Francis developed these successful outlets for their baskets at resorts in the White Mountains, Adirondacks, and elsewhere, may explain why there were less frequent sightings of traveling basketmakers peddling baskets house to

house in Vermont in the second half of the nineteenth century. The Indians were focusing on more lucrative resort markets mostly outside of Vermont. This is a more sensible explanation for the lack of Indian sightings than the idea that they took their identities underground for protection.

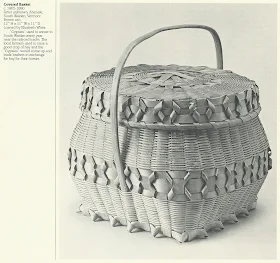

The connection between Indians and basketmaking should not be extended so broadly that it obscures other facts. Just because someone is identified as a basketmaker does not necessarily mean he or she is Indian. There were Yankee baskets of oak splints produced by whites in the second half of the nineteenth century (McMullen 199 1:77). Whites also learned basketmaking from Indians in the nineteenth century and developed their own industries as a result (Brasses 1975:23). Moreover, not only the basketmakers sold baskets. There were also gypsies who bought up baskets front Penobscot Indians in Maine and sold them elsewhere in their travels (Lester, 1987:53, 57). One basket in a Vermont museum is reported to have been traded to a family in northeastern Vermont by gypsies in the late nineteenth century in exchange for hay for the travelers' horses (Vermont Historical Society 1983). 37.37.

Covered Basket

c. 1865 - 1890

Artist unknown, Abenaki

South Walden, Vermont

Brown ash

12" H x 11" W x 11" D

Loaned by Elizabeth White

"Gypsies" used to winder in South Walden every year near the railroad tracks. The local farmers used to raise a good crop of hay and the "Gypsies" would come up and trade baskets in exchange for hay for their horses.

The Vermont Historical Society Museum

Museum Collection And Loans

Museum Number: 1983.12.1 a-b

Date and Place Received: March 23, 1983, Mple

SOURCE: White, Elizabeth S.

Box 574 in West Yarmouth, Mass. 02673

TITLE: Abenaki covered basket

PLACE AND DATE: 186501890, South Walden, Vermont

MEDIUM: Brown Ash

Covered basket made in the Abenaki tradition in South Walden, Vt. about 1865-1890. Slightly flared sides and deep lid. A row of three dimensions weave "cowes" around the three dimensional weave. (Loops out, see diagram above for the weave). Solid ash handle, about 1/2" inch wide. Lid is 1 3/4" to 2" inches deep.

HISTORY: "Carroll White, born in South Walden, Vermont lived on the ancestral farm there. This basket was given to his parents by gypsies (Indians?) in payment for hay for their horses." donor. From Vermont Vital Records: Carroll H. White born on May 31, 1876 in Walden, Vermont, the son James Dodge White (James D. White was born c. 1833 and died on June 18, 1900 in Walden, Vt.) and Sarah E. (nee: Hill) who was born in Walden, Vt. James and Sarah married January 21, 1862 in Hardwick, Vermont. James Dodge White's parents were Robert and Mary (nee: Durant) White of Walden, Vt.

REMARKS: Basket is illustrated on Page 57 of Always in Season: Folk Art and Traditional Culture in Vermont. By Jane Beck, ed. Montpelier; Vermont Council on the Arts, 1982

[Back to Page 54 of the State Response....]

The association of horses and baskets with gypsies is not unusual. Indeed, Romnichel Gypsies from Britain brought horses to the United States from Canada during the decades after 1860 (Salo & Salo 1982:286). And there were gypsies known to live in eastern Canada during that time period (Salo & Salo 1977). Moreover, basketmaking was a common trade for gypsies in New England (Salo & Salo 1982:288-91).

______________

FOOTNOTE:37. The VHS accession sheet notes that the donor made a parenthetical comment that the gypsies who traded the basket may have been Indians. This shows the confusion between gypsies and Indians that has developed in recent years.

In sum, from 1800 to 1860 the sightings of Indians in Vermont represented traveling families from Canada and Maine selling baskets and wares. Such sightings diminished and were unmentioned after 1860 as the Abenakis found better markets in resort towns outside of Vermont. The occasional mention of basketmakers in Vermont after 1860 can be attributed to whites and gypsies who took up the trade.

Rowland Robinson's Indian Friends

Vermont author and illustrator Rowland E. Robinson ( 1834-1900) was known in the late nineteenth century for his naturalistic stories about Vermont. His writings are sometimes cited in support of arguments that the Abenakis maintained a continuous presence in Vermont (Dann 2001 ). Robinson's works are instructive, but not for the proposition that there was an uninterrupted Abenaki presence in Vermont. The Indians about which he wrote were from Odanak/St. Francis.

Robinson lived in Ferrisburgh, at the southern end of Lake Champlain. While his

stories were published as fiction, they are widely acknowledged to be faithful renditions of people, scenes, and events (Collins 1934: 5-6, Martin 1955:11 ). 38. Robinson's stories include a detailed description of the construction of an Indian canoe, Indian folk legends, and many Indian names for places in Vermont. He gleaned this information from Indians with whom he became friends. This is attested to by some of his personal journals and correspondence that are still extant. 39.

___________________

FOOTNOTES:

38. Collins wrote: "Every reader of Robinson will grant, however. that he was one of those Vermonters who seem gifted with the mind of natural-born investigator. Upon readers of Robinson, whether folk-lore, essays, or history, is laid the conviction that here is an author who knows whereof he writes" (Collins 1934:6).

39. His papers are housed at the Rokeby Museum, Ferrisburgh, Vt., and the Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont, Middlebury, Vt.

Gordon Day drew on Robinson's writing as a source of ethnological material (Day writing 1978a). In the following, summary, Day pointed out that the Indians with whom Robinson was familiar were visitors from St. Francis:

Did he know the Indians? According to Collins: "Almost every year small bands of St. Francis Indians ... camped about Vergennes," Vergennes being at the first falls of Otter Creek and close to Robinson's home. In his geographical essay entitled Along Three Rivers, Robinson writing about Lewis Creek said, "I remember visiting with my grandfather a camp of St. Francis Indians, in a piney hollow that divides the South bank." A footnote in his historical sketch of Ferrisburgh, written in 1860, proves that he was already acquainted with John Watso, the Abenaki Indian who became his principal informant. His letter to Manley Hardy of Brewer, Maine. implies that he was still in touch with this informant in 1896. Such direct testimony does not need support, but again Robinson's own work confirms it. The Indian characters whom he introduced into his stories bore family names which were current in the St. Francis band in the 19th century, names like Wadzo, Takwses, and Otodosan. (Day 1978a:37).

Day believed Robinson had seen the Indians from St. Francis coming to sell their baskets in the 1850's (Day 1978a:39). Indeed, the Indians who visited Vermont in Robinson's narratives came to sell baskets and moccasins around the countryside (Robinson 1921a:92, 1921 b:136 ).

Among the indications that the Indians who visited Ferrisburgh and neighboring

Charlotte were not local residents is Robinson's identification of them as "Waubanakee of Saint Francis." In his article on the history of Ferrisburgh in Maria Henenway" Vermont Historical Gazetteer, Robinson related information he personally gathered from "John Watso, or Wadhso, an intelligent Indian of St. Francois" (Robinson 1867:32). This was contemporaneous information from an Abenaki living in 1858. 40. Watso related the history of the departure of Indians from Vermont as follows:

_________________

FOOTNOTE:

40. Collins says that Hememway met Robinson in 1858 and that his essay on was first Ferrisburgh published by her in 1860 (Collins 1934:8-9).